Written by Steve Otieno

UPDATE: Since the writing of this piece, we learned that ICBC pulled out of the Lamu coal-fired power project.

The nostalgic Kenyan town of Lamu once brought in millions of dollars each year in tourism but now finds itself struggling to maintain its traditional lifestyle amid a now-abandoned coal plant and a wave of unfulfilled development promises.

“We were informed that we would have electricity, more jobs would be created, we were happy and hopeful… I only wish we knew what was awaiting us ahead,” said Samia Omar.

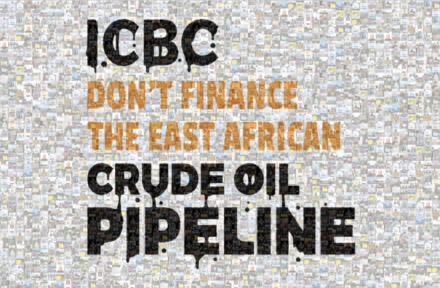

Mrs. Omar, a Lamu resident and one of the leading activists fighting for greater community participation in the region’s development, played a crucial part in blocking the now-abandoned Lamu coal power plant, largely financed by the International and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC).

However, he and many other residents remain frustrated that the promises made to them as part of the Kenyan government’s broader development plan, known as the Lamu Port and LAPSSET Corridor Project, have not come to fruition.

The Lamu Port and LAPSSET Corridor project aimed to connect the three countries in the Eastern Africa region, promising to provide better transportation and access, which could increase the markets between these countries.

Losing its cultural heritage

Lamu is an archipelago and includes several islands where residents maintain traditional fishing methods, including the use of harpoons, basket traps, and the continued use of traditional sailing vessels known as Dhows. These Dhows are stunning, heritage-listed, triangular sailing ships. This adherence to traditional lifestyles also inspires the region’s architecture – coral reefs, palm, and mangrove fronds are key materials in constructing traditional houses.

“It is very expensive to maintain the construction style of Lamu, we use coral stones,” said Omar. However, Samia reflected that it is a culture that “has attracted millions of tourists to its beaches” as “most of the Lamu residents have survived on money from tourists over the past several decades.”

In the end, this desire to maintain a traditional lifestyle and the cultural tourism industry was a key factor of why Samia Omar and many others objected to plans to build the Lamu coal plant.

However, even as the plant has been abandoned, many of Lamu’s traditional practices have been irrevocably changed. This includes their practice of communal farming, which has left Omar in an inter-community conflict.

“Our grandfathers farmed communally. I live in the islands for some parts of the year, then I go to a farm near Kwa Sasi for some time, then back to the island. Last year I farmed here, next time, another place. Then, the coal plant was promised, and land speculators came with it. Who now owns this land? Because it was mine last year. This year, it’s someone else’s,” said Omar.

As a result, she said the project had shifted many of the communal practices in the village and is now worried about how this will impact the village in the future.

“The land titling and individualism that came with colonialism is being strengthened by the whole gold rush for Lamu. The next generation of the people of Lamu, our children, will actually be landless,” she said.

Many of these farmers remain uncertain if they will ever be compensated for the land acquired to build the now abandoned Lamu coal plant, with millions in potential losses.

While the coal plant project didn’t push through, the broader wave of development that it has ushered in has continued to crash against Lamu’s shores, and Samia Omar and many other locals remain swept up in a tide of uncertainty of whether their lives will ever be the same again.

About the author

Stephen “Steve” Otieno Oketch, Kenya

Steve is an investigative reporter at Daily Nation newspaper, owned by the Nation Media Group in Kenya. His favourite thing about being a reporter is discovering secrets and making them known to the public.

He was a finalist at the 9th Annual Journalism Excellency Awards (AJEA) in Kenya and placed 2nd in the Governance category in this year’s AJEA. Stephen is looking forward to linking human rights throughout his stories.

This story was made possible through the support of Climate Tracker.